My Father, A Dynamic Man

Dad was a dynamic man, a man of few words who always managed to teach so much. He was a man of great intellect—a genius, or gen-yi, as our family would say. I always knew this about my dad, but that aspect never defined him.

Dad was a dynamic man, a man of few words who always managed to teach so much. He was a man of great intellect—a genius, or gen-yi, as our family would say. I always knew this about my dad, but that aspect never defined him.

When people asked what my father did for a living, I had a routine answer. I was careful to delicately and slowly allow all of the pieces to surface.

“He’s a professor.”

“Oh. Well, what does he teach?”

“Computer science.”

“Really?! Where?”

“Um, at Yale.”

—Awkward silence—

On paper and without knowing him, my father’s résumé made him sound unapproachable, like he must exist in a different realm than the rest of us. This, of course, couldn’t be farther from the truth. What defined Dad were not the specific lectures that he gave, or the programming languages that he wrote, but the love that he shared, and the belief that he had in each and every one of us. My father was not just a mind and an ego, but a heart and an adventurous soul.

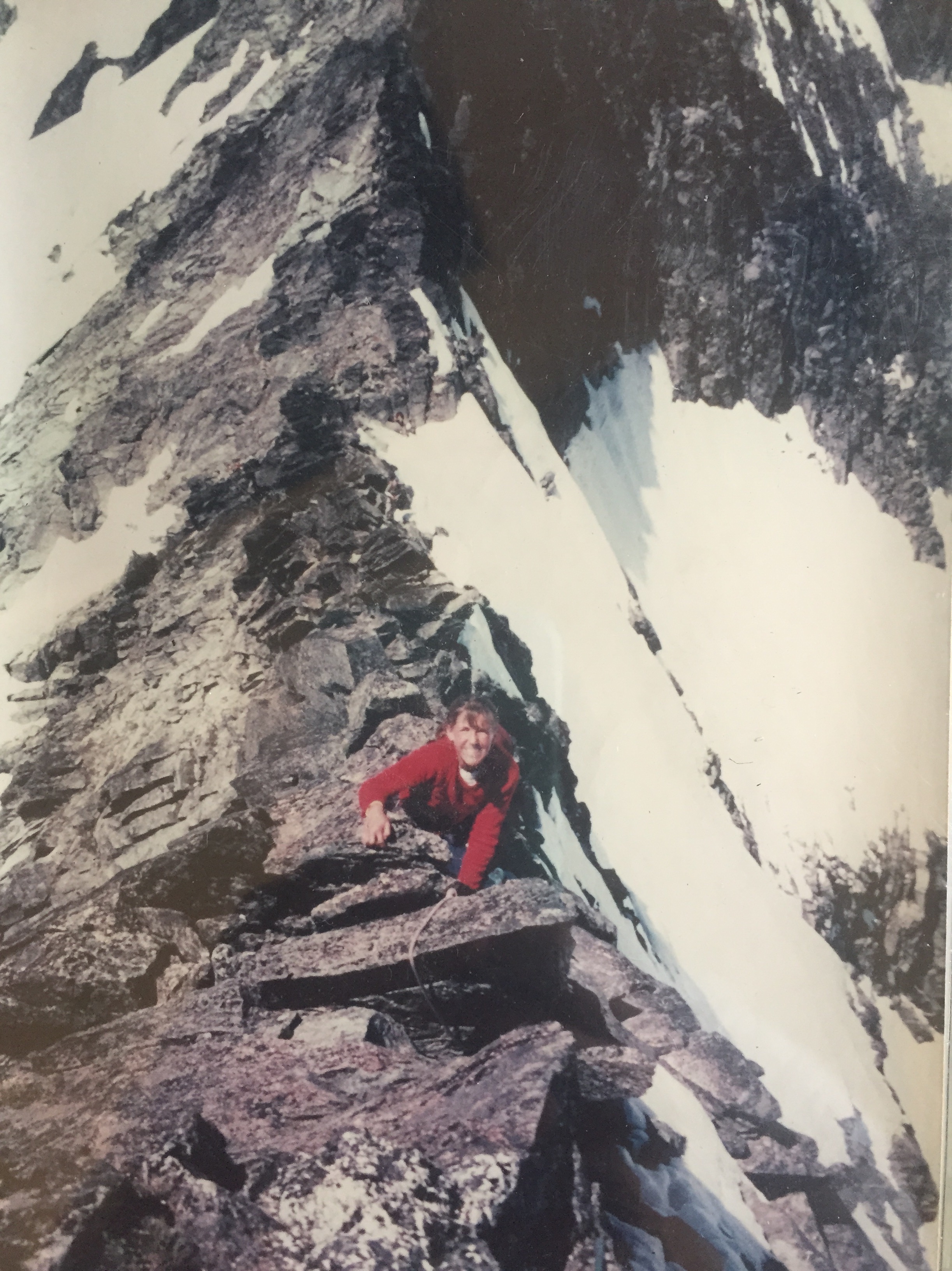

One of the greatest memories that I have with my dad was a mountaineering trip that we went on together with two of his colleagues. I was 12. The trip took place in April of 1999—we climbed Forbidden Peak in Oregon, which involved traveling on glacial terrain. I recently looked up some information about the peak to refresh my memory and laughed at what I learned. The website suggested taking 3 days to make the climb. We did it in two.

The hike in to the base of the climb involved some stream crossings and ultimately landed us on an open glacier with Forbidden Peak towering above. We found the surface of an exposed flat rock about 20’ by 6’ and made that our base camp. We pitched tents on the hard slanted rock because it would be warmer than pitching a tent on snow. In the morning we woke before the sun to begin our summit. It was my first time using an ice axe and crampons and the first time I’d been tethered to someone while “hiking” in case one of us was to slip. I’m not sure that my 110-pound self would’ve been much help to my dad then, but it certainly made me feel safer. The final approach to the summit was an exposed ridgeline with 1,000’ foot drops to either side; I can still generate the butterflies that I felt in my stomach by just thinking back to that view. Standing on the top of that mountain, breathing in the thin fresh air and feeling the warmth of the sun on our face made it all worth it.

But things got interesting on our way out and we came to understand why they recommend taking 3 days to complete the route. As the snow warmed up during the day, it melted into the streams that we crossed the previous day. Those streams had turned into raging rivers by our exit that evening. I remember being passed from shore to shore by my dad and his two friends, one of them would stand in the middle of the river on a semi-stable rock and would transfer me from one river bank to the other. We didn’t get back to our cars until well after dark, but we did something others may have said was impossible. We improvised.

Most fathers wouldn’t think of taking their daughter on such a trip, most wouldn’t imagine their 12 year-old would be up for it, but dad didn’t see me as a young incapable girl, he didn’t look at what I couldn’t or shouldn’t do, but at what would be possible. He saw me as his equal, even at that young age.

Dad believed greatly in human potential. He got you to understand the world better by encouraging you to try a little more, to push a bit harder, to take a leap of faith and attempt something you’d never done before. He facilitated our learning by motivating our trying. This was true whether it was computer science, soccer, lacrosse or jazz.

He lived this philosophy daily as he battled a terrible disease and tolerated relentless side-effects to his treatments. He just kept on trying. I was in awe of his perseverance and courage; I was baffled by his ability to remain positive and to remain kind, to his doctors, nurses, aids and all of us, at least most of the time.

My dad was my hero. Not because of how smart he was, not because of his accomplished career, or for being coach of the year, but because of his ability to love deeply and to share his zest for life with thousands of others—to prove that success in life is so much more than what society lets on. Success is about living passionately, cherishing the little things and reveling in the beauty and light that surrounds us.

My father’s death has left a great mark on my heart. But so too, did his life.